Top 10 risks and opportunities for 2022

8 Feb 2022

Looking back on 2021 it’s interesting to ponder how it will go down in history. Could it be seen as the year that inflation had a momentary resurgence before fading back into the background, or the year that entered us into a new normal? Could it be seen as the year that the 2021 United Nations Climate Change conference (COP26) brought about meaningful climate change mitigation? Could it be seen as the year that sent Chinese stocks into a bear market or the year that provided the buying opportunity of a generation? 2022 will no doubt provide some of the answers to these questions, while likely raising many more.

1. COVID-19 treatments facilitate a return to relative normality

The Omicron variant has led to countries keeping relatively strict containment measures in place, with many countries, particularly in Europe, recently tightening restrictions. However, globally treatments may continue to progress such that living with COVID-19 is increasingly possible. Recent trial results for Pfizer’s PAXLOVID were promising on several fronts. Firstly, it is a treatment for COVID and additionally it is administered orally and can be taken at home, potentially relieving pressure on hospital systems. This, combined with booster vaccinations, could allow broader re-opening, supply chain normalisation and healthcare pressures to ease.

2. De-carbonisation of energy

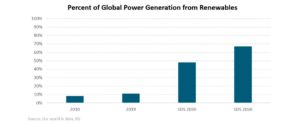

More than 130 countries have now set a target of reducing emissions to net zero by 2050, with many companies and investment funds also committing. To get on track with this target, countries need to cut emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2010 levels, a goal the world is not nearly on track to achieve. Achieving this goal will require a radical change to how we invest, live and produce energy. However, we are seeing green shoots of progress in capital markets; in the first half of 2021 alone there was almost as much money raised for climate-related venture capital funds than any other full year on record with just shy of US$15 billion raised. This only accelerated in H2, with Brookfield on track to raise a US$15 billion climate technology fund, along with numerous others. This will help drive the massive investment needed to get the world to 70% energy renewables by 2050 in the UN’s Sustainable Development Scenarios. Based on the global energy trends below, which show renewables account for just 11% of energy, 2022 must bring about swift progress.

3. Growth vs. Value

Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), market dominance has moved away from asset-heavy companies (think oil companies and banks) and towards higher growth asset-light companies (think companies such as Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet). Part of this shift has seen value companies, most typically characterised as companies with a lower price-to-earnings ratio and low price-to-book ratio, underperform. While the market focus tends to be on the valuation of growth stocks, we think that this ignores some disruptive trends that may negatively impact value stocks more than growth stocks.

As we look forward to 2022, these trends, particularly the energy transition and digitisation, could create value traps over the medium term. The case for strong earnings growth for companies that do continue to invest in technology increases the probability that high quality growth stocks may maintain a large valuation premium.

4. High global inflation persists

Economists and financial markets expect inflation to moderate through 2022 as supply chain disruption eases. The associated reduction in goods prices may mean that tradable inflation for many countries, including New Zealand, may approach zero in 2022 and perhaps become negative in 2023. In the US, annual core inflation is expected to drop from almost 5% currently to around 2.5%. This is also reflected in US breakeven inflation rates (the difference between nominal government bonds and those that provide protection against inflation).

There is a risk, however, that inflation pressures related to supply chain disruption give way to those from rising wages and higher housing rents. Developed economy labour markets are showing signs of tightness. Lower rates of labour force participation have helped US wages increase 4% in the past year, the most since 2004. Early evidence suggests that the US Phillips curve, which plots the relationship between the unemployment rate and wage growth, is much steeper than in the decade that followed the GFC. New Zealand wage growth was 2.5% y/y in Q3, the highest since 2009, and expectations of inflation are 3.0% y/y. Housing rent inflation may also contribute to more persistent inflation. Developed economy house prices have increased notably from their pre-COVID levels. Recent work by the International Monetary Fund suggests that recent house price gains will continue to place upward pressure on rents for years to come. A high inflation environment may see real assets, such as real estate and inflation-linked government bonds outperform. Within the economy, however, it may act to erode consumers’ purchasing power, reduce the real value of savings and distort price signals.

5. More persistent inflation requires more aggressive global monetary policy tightening that may further trouble asset prices

An increasingly hawkish US Federal Reserve has pushed US interest rates notably higher since the end of 2021, providing a challenging environment for equity markets. There may be more to come with the market currently implying that the Fed, BoE and RBA will not increase policy interest rates beyond 2.0% over the next three years, despite neutral policy rates sitting somewhere between 1.5-2.0%. Should inflation prove more persistent, larger tightening cycles may be necessary to tame inflation. Historically, sharp, and unexpected interest rate rises have troubled asset prices. Within an equity risk premium framework, where forward-looking earnings yields are compared to the real return from bonds, the prospect of large increases in real yields may create a challenge for equity markets if earnings aren’t able to beat expectations.

6. New Zealand housing market downfall

Most economists are forecasting very mild declines in house prices in 2022 as the labour market remains tight and economic activity is healthy. While the narrative of lower house prices may have filtered through the equity market, the fixed income market appears sanguine on house price risks. There is still 1.75% of Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) official cash rate (OCR) hikes anticipated over the next 12 months. We think there is a confluence of challenges to the housing market that may result in a larger fall in house prices than fixed income markets expect:

- Higher mortgage rates will challenge buyers and increase debt servicing costs for existing owners. Mortgage rates have already increased 1.5-2.0% and may increase a further 1.0-1.5% over the coming year. The average outstanding mortgage rate is just 2.9%, almost 1.0% below the lowest current rate. Many households will soon be exposed to these higher rates, as about 50 per cent of outstanding mortgages are fixed for less than one year. In the case of a 25-year mortgage, repayments increase by around 10% for every one percentage point increase in mortgage rates.

- Tighter lending standards The RBNZ has increased loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions and is considering the imposition of debt-to-income (DTI) ratio restrictions. The Commerce Commission has also tightened lending standards from December 2021 to require greater verification of loan affordability and suitability under the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act (CCCF Act).

- Unaffordability New Zealand’s house price-to-income ratio is about 11, vs. 5-6 in the early 2000’s.

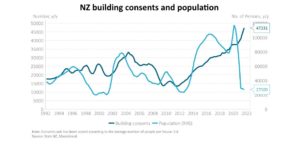

- Housing supply deficit is rapidly being resolved as building consents continue to grow faster than population. This may also be exacerbated if we see net outflows of New Zealanders as borders open.

- Less appealing investment Rental yields have declined. The capital gain bright-line test has been extended from 5 to 10 years and interest costs are no longer allowed to be deducted from taxable income.

7. China eases policy more aggressively in response to the slowing property market

Most analysts recognise that China’s recent prioritisation of its longer-term goals of reducing income inequality, de-carbonisation and deleveraging is likely to cause a slowing in economic growth in 2022. Policy stimulus is expected to be limited and the property sector is likely to be a key source of economic weakness. The Chinese economy is expected to grow by about 5% in 2022, versus an average of almost 7% y/y in the five years prior to 2019.

Greater-than-expected policy support, however, may result in higher economic growth and present an opportunity for investors in 2022. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) reduced key policy rates in January. This might represent the beginning of a shift in policy priority from some of China’s longer-term goals to supporting the economy.

8. Equity markets deliver double digit returns

If you feel like 2021 was rare period of high returns, your feeling is right. The market gained over 20%, with the maximum peak-to-trough loss during the year being just 5%, compared to the average fall of 14% since 1980. That, combined with the soggy start we’ve had in 2022, may make one think we are due for a big correction, but history would beg to differ. 2021 was the third time post WW2 that shares have had back-to-back 20% years (if we include the US market as a barometer).

Bottom line: Bull markets don’t die of old age. While equity market gains were strong in 2021, the gains were relatively concentrated across major indices. For example, over 50% of the Nasdaq’s 2021 gain was down to two stocks, whilst the New Zealand market was down in 2021. Chinese stocks also fell in 2021 due to regulatory concerns as well as concerns around the delisting of ADRs (American Depositary Receipts – instruments that allow Chinese companies to list in the US). While it is easy to focus on the downside given the start to the year, a bounce back from the more unloved parts of the market, the resumption of buybacks and a capex boom are all potential upside risks for 2022.

9. Geopolitics

Tensions between Russia and Ukraine are high, and a partial re-invasion of Ukraine is possible in 2022. Ukraine offers strategic value to Russia as a land buffer to potential invaders and for access to the Black Sea. Russia has amassed large numbers of troops on the Ukrainian border in recent months and the military balance heavily favours Russia. Western country sanctions since 2014 have done little to change Russia’s approach to Ukraine and the threat of additional sanctions may not be enough to stop conflict. In the event of re-invasion and the imposition of additional sanctions, Russia may choose to limit energy exports at a time where the global energy supply is already under pressure, particularly in Europe. This could create additional global inflation pressure and damage economic activity.

10. Increased volatility

Given the plethora of risks over the coming year, financial markets appear somewhat complacent. The value of the Australian dollar versus the Japanese Yen (AUD/JPY) is often used as a proxy for risk sentiment. Australia is seen as being highly sensitive to global growth prospects and investor sentiment. It is an open economy with a reliance on the rest of the world to fund it. Japan, in contrast, is seen as a “safe haven”. Its economy is relatively closed, and it is a net provider of savings to the world. We can use the price of 1-year AUD/JPY options (derivatives that give the holder the opportunity to buy or sell AUD/JPY in one year’s time at a rate determined today) as an indication of expected volatility over the coming year. This implied volatility is currently well below its post-GFC average.

Any 12-month period has scope for large surprises, COVID-19 has taught us that. The lesson is to be ready for change, have a culture that enables adaptation and to ensure adequate access to liquidity.

Any views expressed in this article are the personal views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of BNZ, or its related entities.

This article is solely for information purposes and is not intended to be financial advice. If you need help, please contact BNZ or your financial adviser. Neither Bank of New Zealand nor any person involved in this article accepts any liability for any loss or damage whatsoever which may directly or indirectly result from any, information, representation or omission, whether negligent or otherwise, contained in this article.