Year of the refix

22 Jan 2025

- Shifting US interest rate expectations important, but NZIER survey reaffirms NZ is different

- No change to our interest rate expectations

- Outstanding mortgage book shortest in 13 years; 81% of borrowings to reprice in the coming 12 months

- Fixing decision perhaps not as clear cut as this sort of positioning would imply

In amongst the vagaries of the New Year news flow, a couple of things have stood out to us (meme coins aside). The first is the continued, volatile, upward trend in offshore long-term interest rates. The second is how short the average tenor of NZ mortgage borrowing has become.

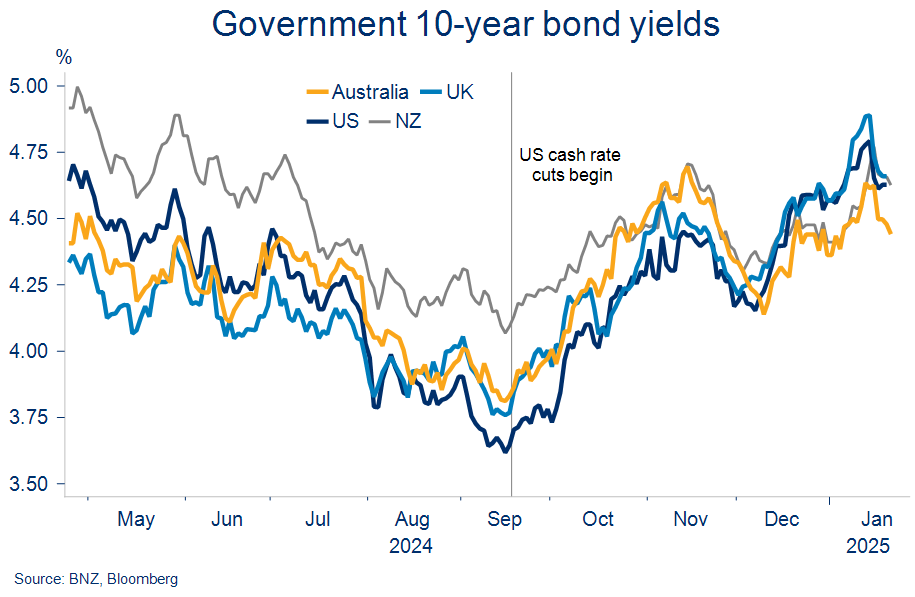

On the first, even though most of the big offshore central banks are still lowering their cash rates, long-term bond yields have generally been trending in the other direction. That’s a tad unusual historically.

Driving the moves, which have been most prominent in the US and UK, has been some combination of concerns about fiscal sustainability, higher risk premia associated with Trump’s uncertain policy agenda, and a growing sense that the US Federal Reserve may have run out of room to keeping cutting interest rates. The consensus is now for only one more 25bps rate cut by the Fed this year.

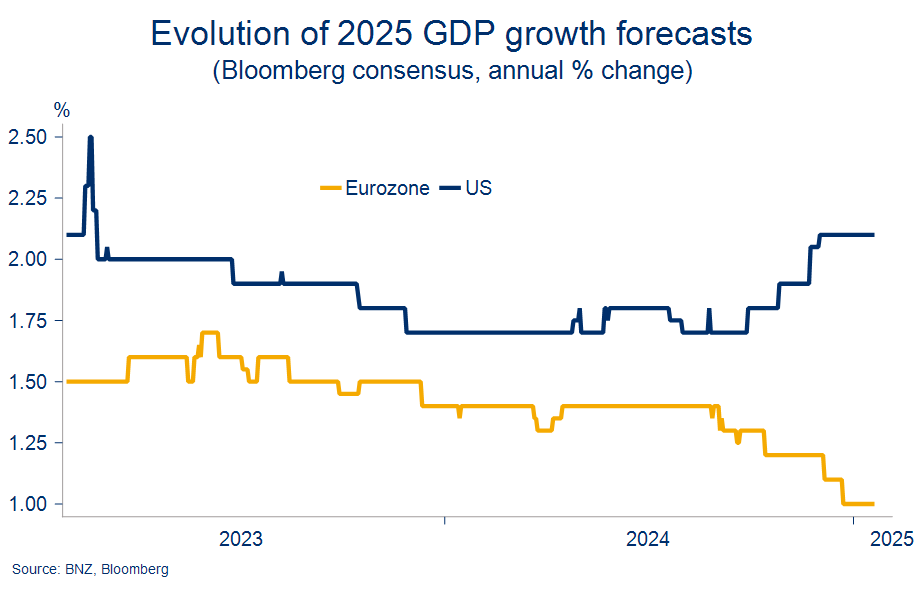

This shortening of the US rate cut runway seems appropriate given underlying US inflation looks to be bottoming out in a 2½ -3% range, a little above the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This partly reflects the fact the US economy simply refuses to lie down. Forecasters are in the process of upgrading the 2025 US economic prognosis from a ‘soft landing’ to a ‘no landing’ scenario, even as forecasts for most other major economies get the snip.

An earlier end to the US rate cutting cycle would have implications for NZ. Longer-term NZ wholesale interest rates would face less downside pressure given their close relationship to US equivalents, and the NZ dollar could be expected to track lower than otherwise with the US dollar in the ascendancy.

We’re of course seeing some of the latter already. The NZD/USD recently touched a 15½ year low around 0.5550, before recovering a little. A lower NZD is helpful for the export sector, at least to the extent currency exposures are not already hedged. But it also entails a little more imported inflation than otherwise.

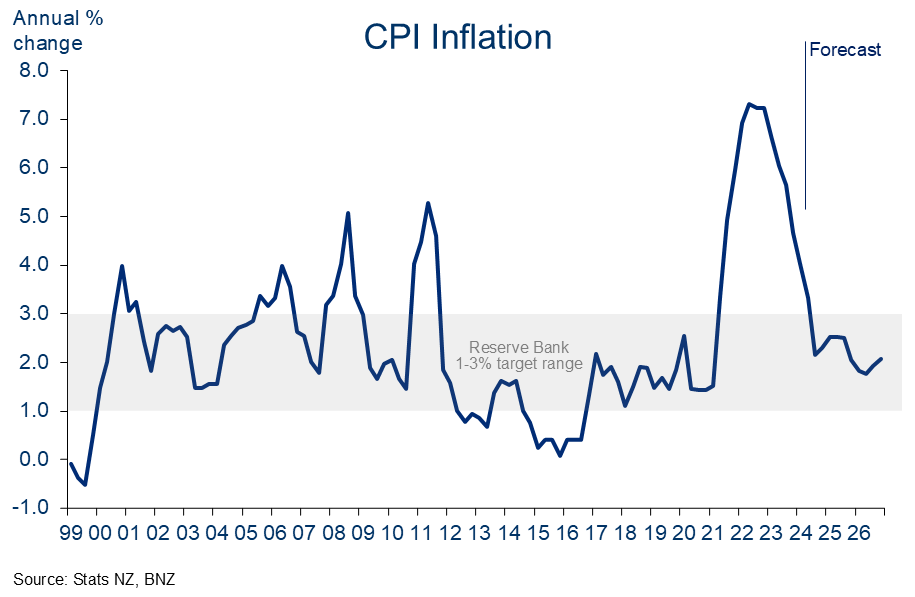

We’ve recently nudged up our short-term inflation forecasts, mainly on account of higher oil/petrol prices, with upside risk from the lower NZD. We now see first quarter CPI inflation of 2.5%y/y (up from 2.2% previously). Later this morning we’ll receive CPI figures for the final quarter of 2024. We’re expecting a tick up from 2.2% to a 2.3% annual print.

These short-term inflation niggles are naturally unwelcome but won’t be overly bothersome for the Reserve Bank in our view. That’s contingent on limited flow-on effects to wider price setting behaviour. Our broader contention that inflation is under control remains very much intact, with a gradual return to the 2% target midpoint slated for late 2025/early 2026.

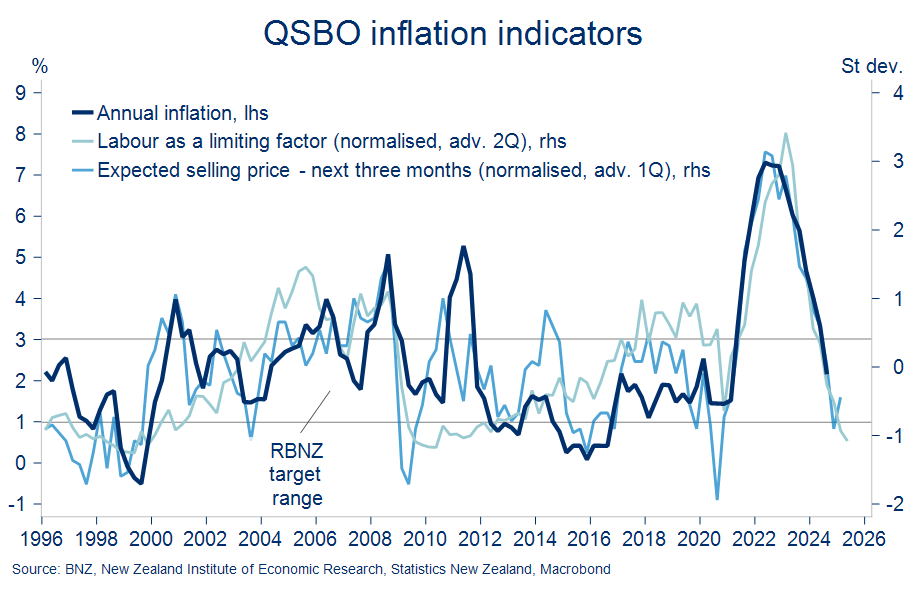

Support for this view was our main takeaway from the only top-tier local data release of 2025 so far, last week’s quarterly business survey from the NZIER. None of the survey readings were particularly surprising. But there was still an important reassertion of the notion ‘NZ is different’, given some speculation that changes in US rate cut expectations could produce something similar in NZ.

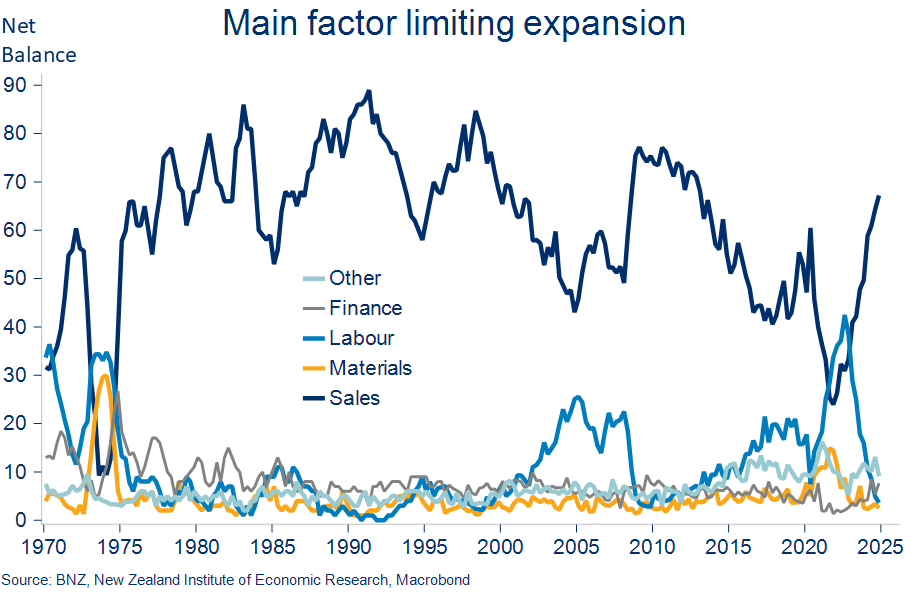

Businesses are more confident growth will resume this year, bringing about some improvement in currently dire profitability. That’s consistent with our forecasts for a modest 1.2% expansion in economic output over 2025. But firms don’t expect this to allow widespread increases in selling prices. Only a net 15% of firms expect to raise their selling price over the coming three months.

Spare capacity abounds, in other words, and customer demand is still very weak. “Sales” are the most commonly reported limiting factor for 67% of firms, with daylight to all the others (and more so than average). Against this backdrop, the survey’s inflation indicators continue to depict a short-term underlying inflation pulse no higher than 2% (second chart below).

The clear shortfall in demand, alongside at-target inflation, accords with our view that the Reserve Bank’s cash rate still needs to fall from here. We haven’t changed our forecasts for such. We expect a third straight 50bps cut in February, taking the cash rate to 3.75%.

Our forecasts thereafter are for a series of more regulation 25bps cuts as the RBNZ feels its way on the nebulous ‘neutral’ cash rate. The pace and timing of additional cuts following the strong chance of a February 50-pointer has always been highly uncertain but is probably more so now given developments in US interest rate markets. A string of incoming US policy announcements, with trade policy front and centre, further clouds the picture.

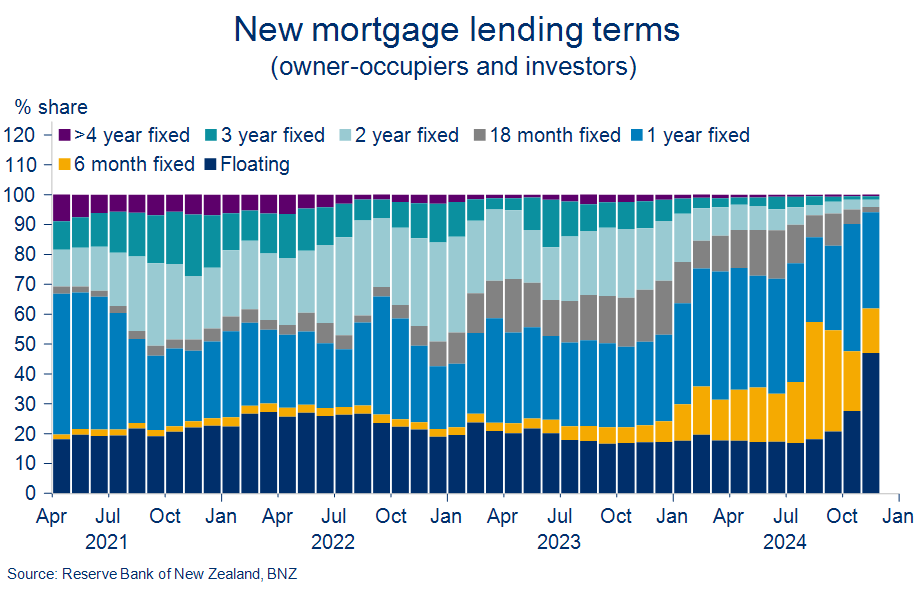

Against this backdrop, we noted with interest how skewed towards shorter terms the mortgage book has become in figures reported by the RBNZ last week. The prior clamour for short terms is becoming a stampede.

Almost half (47%) of all new mortgage lending in November was on a floating term. This preference for floating was widespread but slightly more concentrated amongst investors (51% of new lending).

If new borrowing wasn’t on floating terms in November it was for short fixed terms such that only 6% of new lending during the month was for a term of 12 months or more. It seems reasonable to assume these trends continued at least through December given the Reserve Bank’s guidance toward a February 50bp cash rate cut would have still been ringing in borrowers’ ears.

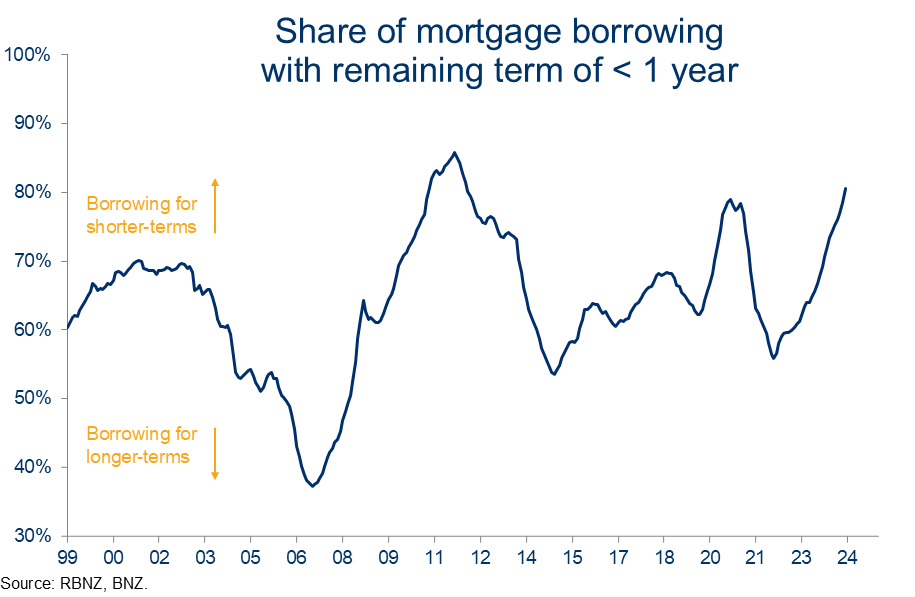

This ongoing rush into shorter terms has slowly but surely tilted the stock of existing mortgage debt. The share of the mortgage book on floating rates has lifted from 10% to 15% while the share of outstanding mortgage borrowing with a maturity of less than 12 months is now 81%. In data going back to 1999 that’s only been matched once before, in 2011/12.

To date, going short has tended to pay off given aggressive cuts to the cash rate and associated falls in mortgage rates. Indeed, as we flagged last year, borrowers broke with historical precedent and positioned for the rate cutting cycle well in advance of it actually turning up. That’s even though it cost more upfront to do so.

Moreover, mortgage-holders will continue to benefit to the extent there are further reductions in the OCR along the lines of our forecasts. These imply, at face-value, six month and one-year mortgage rates falling below 5% by around mid-year.

At the same time though, we’re compelled to offer a few competing viewpoints. First, a borrowing strategy concentrated at shorter-terms means a higher share of future interest expense is ‘at risk’. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing of course. But it does increase exposure to any unanticipated shocks in a year in which we could see a few. The volatile start to the year in financial markets is a reminder of such.

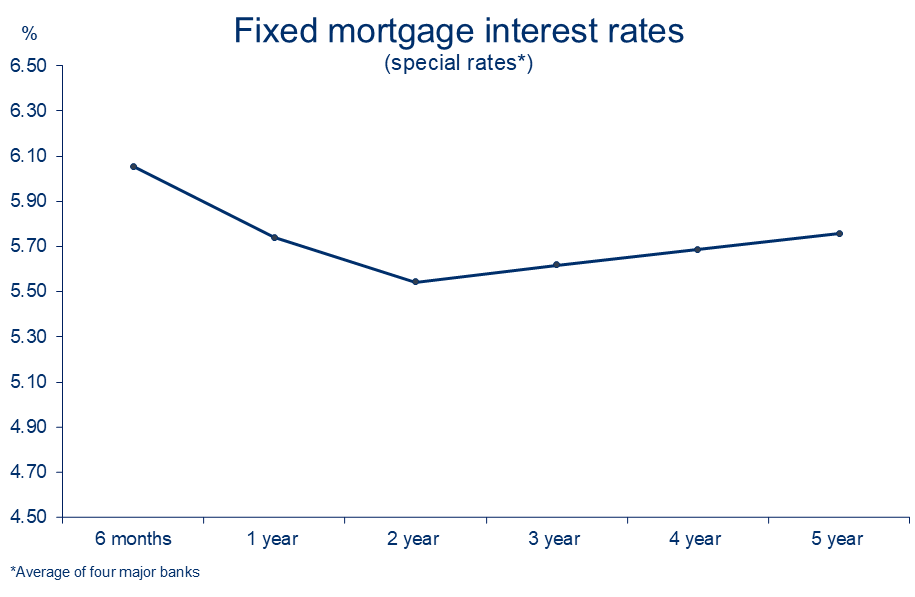

Second, a swathe of Reserve Bank cash rate cuts are already factored into interest rates where they stand. This presents both risks and opportunities.

For example, expectations of a much lower OCR in six-months’ time means six-month fixed mortgage rates are about 1.3% lower than floating rates. Given this, we’re a little surprised the preference to float is so strong. Floating has the benefit of extra flexibility, but the large rate difference increases the bar to breaking even relative to fixing for a six month term.

Chunky rate cut expectations are also holding term mortgage rates like the two-year below those of shorter-terms. The former encapsulate market expectations of a longer period of a lower OCR. But this also means the hurdle for further trend declines in these term rates is higher.

That is, for the two-year rate to fall further from here requires not just the OCR be cut further, but that current expectations for more than 100bps worth of cuts are dialled up. This plays to the grain of our view that there is still some downside in term (two, three year) rates but probably not as much as some think.

It’s something to think about for those on short terms as they ponder an appropriate time to term-out some of their debt. Added to this is the fact that remaining on short-terms costs more upfront, with the ultimate benefit – being able to roll onto lower rates in future – uncertain.

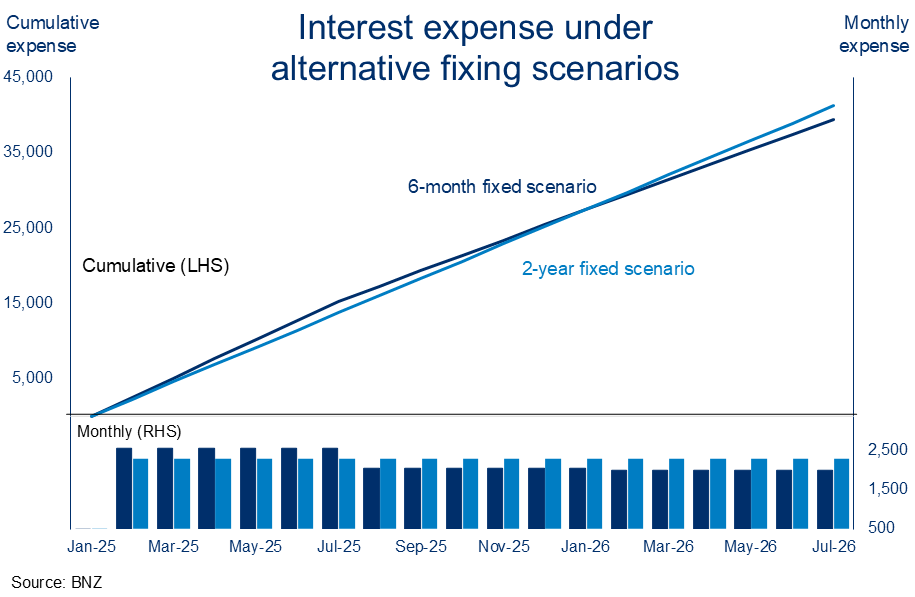

A simplified example illustrates the point. The chart shows the monthly and cumulative cost of fixing today for either two-years or six months on a hypothetical 500k debt. You can fix for two-years at the current rate around 5.5%, entailing a constant $2300 monthly interest cost. Or fix for six-months at a higher rate of around 6.1%, on the expectation you can hopefully re-fix at lower rates in future. In the chart below we’ve assumed the first six-monthly refix in August 2025 is at 4.9% and the second in February 2026 at 4.8%.

The chart shows that the cumulative interest cost “worm” on the six month option eventually falls below the two-year one but: 1) it takes a while – until January 2026 – and, 2), that relies on the decent falls in six month rates we’ve

assumed. This analysis also makes no allowance for the extra utility a borrower might get (sleep quality?) under the more highly hedged, two-year fixed scenario.

The point is that, while mortgage borrowing for short terms may make sense given the potential for additional short-term rate relief, to us, fixing for tenors longer than a year does not look as unappealing as the current meagre demand would imply. We’re only 22 days in but the fact that this year is looking particularly unpredictable highlights the point. There are risks aplenty.

To subscribe to Mike’s updates click here

Disclaimer: This publication has been produced by Bank of New Zealand (BNZ). This publication accurately reflects the personal views of the author about the subject matters discussed, and is based upon sources reasonably believed to be reliable and accurate. The views of the author do not necessarily reflect the views of BNZ. No part of the compensation of the author was, is, or will be, directly or indirectly, related to any specific recommendations or views expressed. The information in this publication is solely for information purposes and is not intended to be financial advice. If you need help, please contact BNZ or your financial adviser. Any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance, and no statements as to future matters are guaranteed to be accurate or reliable. To the maximum extent permissible by law, neither BNZ nor any person involved in this publication accepts any liability for any loss or damage whatsoever which may directly or indirectly result from any, opinion, information, representation or omission, whether negligent or otherwise, contained in this publication.